Not for the first time, Jason Karp has found himself in the right place at the right time.

He had the good fortune to be in the hedge fund industry during its boom following the 2008 financial crisis. He grew his fund, Tourbillon Capital Partners, to a sizeable $4bn in assets.

Then last year, he wound down the New York-based business, moved with his family to Texas and decided to devote his entrepreneurial energies to the health sector.

Now aged 43, Karp was inspired to act by his own experience battling autoimmune diseases that had threatened to leave him blind two decades earlier. But his timing could not have been better, with the Covid-19 pandemic highlighting the importance and investment potential of healthcare and health-related businesses.

Karp’s venture, HumanCo, is styled as a Berkshire Hathaway-like holding company focused on good-for-you consumer goods. Karp plans to make new investments in products such as his Hu line of chocolate bars, which are made without refined sugars and other additives, and the Oura Ring, a sleep-tracking device. “I’m more excited than ever that the world needs this, and I think the crisis is a wake-up call,” says Karp.

Analysts say demand for virtual healthcare, spurred on by insurance rules relaxed during the crisis, could outlast the pandemic

Karp’s story is one example of how Covid-19 has created new opportunity for wealthy individuals directing their money to health-related ventures. For some it is all about money, but for others, including Karp, the projects blend profit and a desire for social impact.

“What [the investment community] needs to do is pour money into research,” says Ron Conway, the prolific Silicon Valley start-up investor and philanthropist who has made early bets on companies including travel group Airbnb. “If it’s a not-for-profit, they need to get out their personal pocketbook and donate. And yes, every [venture capitalist] I know is doing that.”

Deep-pocketed backers are seeking opportunities in everything from remote-healthcare apps to new drugs targeting coronavirus, and they have capital at the ready. Tiger 21, a US-based club for multimillionaires, estimates that wealthy investors in its network started the year with 12 per cent of their assets in cash, out of a total of $72bn.

Demand has surged for remote healthcare

Healthcare is already familiar territory to many. The sector has been a popular trade in the past decade, outpacing even the strong bull market for US stocks. Healthcare companies in the S&P 500 index rose 240 per cent in the decade to mid-May 2020, compared with 140 per cent for the index as a whole.

Ageing populations in the developed world, advances in medical technology and expensive blockbuster drugs targeting cancer and other diseases have all drawn investor attention, both to listed companies and risky start-ups.

In the first quarter of this year alone, healthcare start-ups raised more than $14.6bn globally — the highest levels since 2018, according to the data provider CB Insights. Total healthcare funding reached almost $54.7bn last year.

The healthcare sector has held up even as the pandemic triggered shocks in financial markets. By late May, healthcare stocks in the S&P 500 were up almost 6 per cent on the year, compared with a slight drop in the broader index. Meanwhile, companies with promising products linked to Covid-19 have soared, including biotech groups such as Gilead Sciences and Moderna, which have announced positive news on vaccine developments.

Their popularity is fuelled by the overwhelming drive to tackle Covid-19, combined with a huge increase in government healthcare spending. Even before the pandemic, consultancy Deloitte forecast a 5 per cent annual increase in global health spending in the years to 2023.

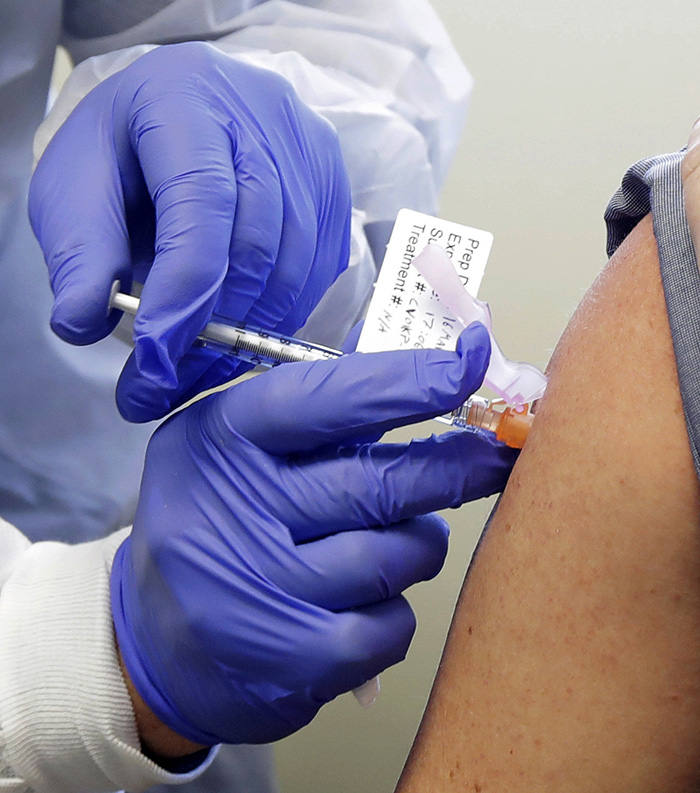

A trial participant receives a potential Covid-19 vaccine developed

by US company Moderna

“With Covid, we see that healthcare and life sciences companies are going to have a tailwind behind them,” says Chris Ivey, head of the European private client practice at Cambridge Associates, the US investment company. Ivey says his wealthy clients are especially interested in backing start-ups creating new products that could become acquisition targets for big pharmaceutical groups.

But some investors warn that new ventures such as vaccine developers are risky bets, and start-ups aimed at preventing diseases such as the new coronavirus have so far produced little financial return.

“Anti-infective drug development has been a terrible place to invest for about 10 years,” says Bryan Roberts, a California-based partner at venture capital firm Venrock, which invests in healthcare. Before the pandemic, several well-funded start-ups in the sector, such as Achaogen and Melinta, filed for bankruptcy. “The commercial model is really hard,” says Roberts.

If you have a great vaccine, there’s probably not enough money in therapies

Bryan Roberts, partner at venture capital firm Venrock

Others are betting that with Covid-19 it will be different. Swiss private banks Julius Baer and Pictet both invested in Moderna before its initial public offering two years ago, giving their wealthy clients an early foothold in what is widely considered to be one of the leaders in the race for a vaccine.

Meanwhile, Jim Simons, the billionaire founder of hedge fund Renaissance Technologies, drew headlines in February for supporting the rival vaccine developer Codagenix through his family office Euclidean Capital.

Conway, the Silicon Valley-based investor, says his SV Angel funds have invested in “very nascent technologies that are working on Covid and other related diseases” which have yet to launch officially. They are also evaluating companies working on drugs to treat Covid-19, having previously made few investments in therapeutics ventures.

Other investors see an approach focused narrowly on Covid-19 as too risky. A successful vaccine would quickly eliminate the need for most treatments, with fewer people catching the disease.

“One of the risks of investing in this space is, how long-lived is the product?” says Roberts. “If you have a great vaccine, there’s probably not enough money in therapies on a go-forward basis because not many people get it.” Instead, Roberts and other healthcare investors have targeted companies benefiting from an expected broad increase in health-related spending they think the pandemic will bring.

Karp is one such investor. He came to the health sector after suffering from illnesses before the age of 30 that forced him to reconsider his life and adopt a healthier lifestyle. He cut out caffeine, alcohol, refined sugar and other processed foods, and taught himself how to sleep again after developing insomnia.

He then turned his attention to the role of large food conglomerates in the American diet. With his brother-in-law Jordan Brown, a property developer, he consulted food experts on launching a restaurant and a line of packaged goods that used minimally processed ingredients. “The evolution over the last 50 years has been toward what shareholders have wanted, which is scale, shelf life, low price and distribution,” Karp says.

Citing a University of North Carolina study, Karp says just 12 per cent of Americans are considered metabolically healthy, creating a large market opportunity for HumanCo to supply better-quality products he says will improve wellbeing and lower future healthcare costs.

Working from his new Texas home, Karp now finds himself evaluating at least one new business proposal every day. In January, HumanCo received $15m in backing from more than 30 investors, led by Karp and his college friend, Brian Sheth, the billionaire president of Austin-based software investment firm Vista Equity Partners.

Karp thinks HumanCo’s healthy foods can help prevent the chronic conditions that put people at greater risk of dying from coronavirus. “What’s clear is when you have a lot of body-wide systemic inflammation, your body’s ability to fight and heal is just inferior,” he says.

Meanwhile, other venture capitalists are predicting online apps can upend the healthcare system. Under the broad moniker of “telehealth”, these companies do everything from delivering primary care over the internet to shipping medication directly to consumers.

While some such companies have been around for years, the Covid-19 crisis has sped up their development. Telehealth start-ups completed 103 funding rounds totalling $1.6bn in the first quarter of 2020, more than double the number of deals that took place in the fourth quarter last year, according to CB Insights.

Some big names are backing the sector, notably Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos, whose Bezos Expeditions family office has invested in ZocDoc, an online registry allowing users to book doctor appointments and remote check-ups.

Many remote-healthcare providers have seen a surge in demand as authorities encourage patients to avoid hospitals and doctors’ surgeries. Medici, a US tele-health start-up, posted a 1,409 per cent increase in patient registrations between February and April, when it raised $24m in new funding from billionaires including property investor Barry Sternlicht and hedge fund manager Ken Griffin.

Hims & Hers founders Hilary Coles and Andrew Dudum

Roman Health and Hims & Hers, two rival US start-ups that sell cosmetic and sexual health prescriptions online, have both looked to raise new funding since the epidemic broke out, according to people briefed on their plans. Hims & Hers, known originally as just Hims, focused initially on the male market, but co-founder Hilary Coles has led the introduction of products targeted at women, including hair-loss treatments and sexual disorder drug Addyi.

The company, which last year reached a $1bn valuation, in May began shipping an at-home Covid-19 test approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, offering it on an at-cost basis of $150.

Healthcare analysts say demand for virtual healthcare services, spurred by relaxed insurance rules enacted during the crisis, could outlast the pandemic. CB Insights analyst Marissa Schlueter points to policy changes that have driven adoption. “We’re in a period where we can be generating a lot of buy-in and enhanced value to the overall healthcare system,” she says.

Some private bankers warn that healthcare companies have become expensive following a decade of rising valuations, and picking winners often requires specialist scientific knowledge. “The train has often already left the station,” says one Swiss wealth management executive. Shares in Moderna, for example, had risen 212 per cent between the start of the year and early June.

But following a rise in funding, biotech companies have plenty of capital to complete new drug trials and create new sources of revenue, says Anastasia Amoroso, head of cross-asset thematic strategy at JPMorgan Private Bank.

She says wealthy clients can see the impact of their investments in healthcare companies on real-world problems. “Clearly the desire for change and the desire for financial returns are well aligned at the moment.”

Read original article here